I have the intentions in Yexus Communitas to provide a series of historical reflections that can help process our thoughts between history and the church, and more specifically its connection to the Hmong church’s reality. To begin, the study of history is the understanding that the historical human experience is a complicated yet original task. Occasionally, it’s easy to draw connections between the historical Christian experience and the present church. But most of the time, as a result of context, human sin, and depravity, the historical Christian experience is a complicated subject to relate to. Through a reflective blog series, I will reflect on the historical originalities and complications of the past and rethink it through the lenses of the Hmong Christian experience.

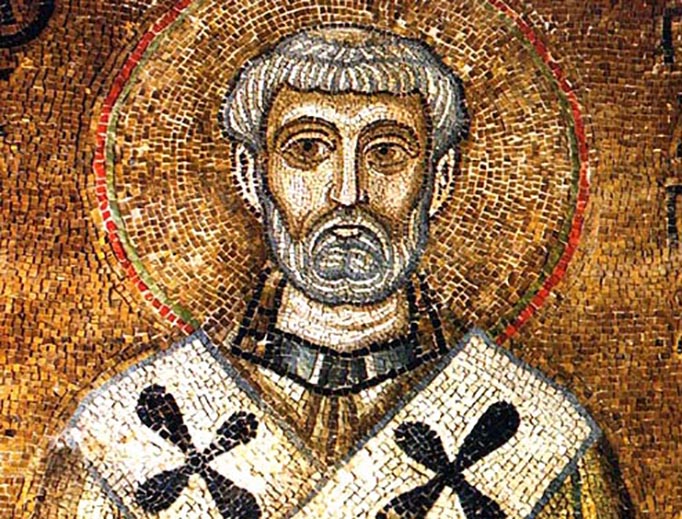

These historical reflections will begin chronologically. The first chronological figure that I want to examine is Clement of Rome (30 A.D.- 100 A.D. approx.), one of the first apostolic successors and Church Fathers of the Early Church. He became known for his First and Second Letter to the Corinthian Church at around 95 A.D. where his letters have been passed on by many other churches. The letters were close to becoming a part of the Bible during the canonical processes of the Early Church, but because of his minimal references to the Apocryphal texts and his lack of intimate connections with the other Apostles (only being a successor to them), his work became accepted as canonical by a few and non-canonical by others.[1] However, Clement of Rome’s work has been helpful in understanding the contexts of the Corinthian church after the ministries of Paul. This article specifically aims to explain how the writings of Clement of Rome can help us to better understand modern-day Hmong leadership in the church. The First Letter will be used to explain my reflections.

The context of the First Letter to the Corinthian Church is that the church had been facing a leadership crisis. Some of the intellectual congregants (or “rivals”) according to Clement believed that the bishop, priest or pastor is equal to everybody in the church and that the pastor is no different from a saved believer because of sin. Consequently, this belief encouraged a notion that the priest or pastor is not to be held in high regard in the church. Therefore, they should be treated as a regular congregant with speaking abilities about scripture, but with no principle of divine authority or ordination whatsoever.[2] However, Clement wanted to reiterate in his letter that the priest or pastorate position is an ordained position by God and that it has apostolic roots in its formation.[3] Whoever stems from these roots are considered a part of the apostolic lineage, and are therefore ordained ministers of God:

“The apostles received the Gospel for us from the Lord Jesus Christ…Thus Christ is from God and the apostles from Christ. In both instances, the orderly procedure depends on God’s will…They preached in country and city, and appointed their first converts, after testing them by the Spirit, to be the bishops and deacons of future believers.”[4]

How does this relate to the Hmong church today? From my observations, Hmong church leadership is currently facing an upcoming transition where non-pastoral leaders (especially women) are rising in the church due to education, politics, and influence. Currently, their participation in leadership is still minimal. But when I look at myself alongside with many others second-generation Hmong Christians who are pursuing scholarly, secular, or Christian leadership without the intention of filling an official pastoral role, it’s inevitable that our participation will rise in the church alongside the temptation for power. The danger of our knowledge and leadership skills is that it can create possible frustrations and perhaps lead individuals to challenge equality with the pastorate position.

The most common perspective within Hmong churches is the understanding that pastors are supposed to be greatly honored in the church. The top-down traditional leadership structure is still present in many Hmong churches, with all major decisions still moderated by the pastor. We recently had a Pastor Appreciation Day during in our October Sunday service at Twin Cities Hmong Alliance Church. K. Xf. Tswv Hlau Yang (Senior Pastor), Xf. Shoua Yang (Youth Pastor), and my brother Xf. Fong Xiong (Worship Pastor) had all been celebrated for their service to the church. However, because of my knowledge of church history and seeing the flaws of pastors and their work, I have to be honest when I share that I personally began to question the idea of celebrating pastors, wondering if this ritual should be abandoned. I believe some Hmong congregants are starting to ask this same question, too. It’s at this juncture that I began to wonder if perhaps the intellectual congregants or rivals that Clement had faced had logical reasoning with their assumptions.

When we look at 1 Timothy, we begin to see where Clement was trying to reiterate from and that he most likely got Timothy’s letter during his pastorate despite not referencing it.[5] He wanted to show where pastoral ordination began, stating that it began with Jesus and the apostles, just like Paul commissioning Timothy to remain in Ephesus to pastor the congregants from false teachers.[6] The pastorate is an ordained position commission by God from the apostles to the next. If they’re not connected with that lineage, they are not pastors, to begin with, and should be questioned wholeheartedly. It’s here that we come to the beautiful truth that our pastors come from that source if they present the Gospel truth of Christ fluently in its foundations from the Word of God. Therefore, our job as the church is to respect and be accountable with that notion no matter what position or level of education we have. Despite theological, denominational, or communal divides currently happening, the pastoral position must be respected and separated from the congregation in terms of role, for that person is rooted to the Word and to the apostles who came before them.

Therefore, it’s important for us, especially for young Hmong Christian leaders who do not desire to become pastors but are desiring to be intellectuals or leaders in service of the church, to ask ourselves honestly: Have we been humbling ourselves amidst the pastor’s role or trying to take the pastor’s role for ourselves? An examination of the heart and mind will be needed, and many prayers included.

Kou Xiong is a Wheaton College Graduate School grad in History. His focus is on the Modern Church and Chinese Christianity, with an emphasis on early 20th century Chinese Republican Christianity and minorities. He recently received his MA in Church History at Wheaton College, IL in 2016 and is now currently participating at Twin Cities Hmong Alliance Church in Minnesota, serving in the Young Adult ministry. He recently presented at the Conference on Faith and History and is establishing and teaching a Church History 101 lecture series with the TC young adults and has plans to expand the work in the future. Also, he occasionally volunteers with a Christian non-profit English ministry in the University of Minnesota called Connexions International, doing Bible-based English tutoring to International students at an assistant level. Despite being in discernment with his Ph.D. or future academic plans, Kou Xiong has a desire to be a resource for the church in the areas of Christian History, especially in Asian Christianity and foundational Historical Theology.

[1] See J.B Lightfoot, S. Clement of Rome: An Appendix (London: MacMillan and Co., 1877), 275-279.

[2] Clement I, “The First Epistles of Clement to the Corinthian Church,” in Early Christian Fathers, ed. Cyril C. Richardson (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1953), 43-45.

[3] Ibid, 63-65.

[4] Clement I, 62-63.

[5] The First and Second letter to Timothy had not been considered canon until the 3rd Century. As for Clement receiving the First and Second letter to Timothy, the evidence remains ambiguous because of a lack of sources, but his language in the letter could specify that he did. See Gary M. Burge, Andrew E. Hill, ed., The Baker Illustrated Bible Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing Group, 2012), 1455.

[6] 1 Timothy 1:3-7, 18-19, 5:11-16. (NIV)